L'expérience du temps retentit dans la profondeur du mythe. L'œuvre de Jünger poursuit, par ses propres voies, ce récitatif de l'expérience du temps. La réminiscence dans l’œuvre de Marcel Proust, la dilatation temporelle aux dimensions odysséennes d'une seule journée qu’opère James Joyce dans Ulysses, ou encore la récapitulation du monde à la fois joyeuse et apocalyptique des Cantos d’Ezra Pound ravivent dans la littérature moderne ce questionnement immémorial. Comme ceux-là, Jünger n'a cessé d'éprouver la nécessité d'aller au cœur de l'être et du temps et de trouver son propre lieu et sa propre formule pour déchiffrer le monde. Plus que d'autres, Jünger s'est tourné vers le monde pour en déchiffrer les énigmes intérieures.

Si Jünger fut dandy, comme certains persistent à l'en accuser, il faut bien reconnaître que son œuvre est la moins narcissique qui soit. Chaque page de Jünger nous apporte, comme les poèmes de Cendrars, des « nouvelles du monde ». Les paysages les plus grandioses et les aventures les plus extrêmes comme les détails les plus infimes et les circonstances en apparence les moins décisives sont portés à notre attention avec la même déférence, pour peu qu'ils soient les instruments d'une connaissance qualitative, sensible, propice aux aventures de la pensée.

Ruskin définit le véritable artiste à la fois comme « déchiffreur, chanteur et mémorialiste ». Si la part à proprement parler « lyrique » de l'œuvre de Jünger est plus sous-jacente qu'apparente (mais le lyrisme alors n'en touche que les cordes plus profondes, comme dans les dernières pages de Visite à Godenholm,) l'appellation de « déchiffreur » non moins que celle de « mémorialiste » donne immédiatement l'idée la plus juste du propos et du style de ses livres, qui paraissent, par ailleurs, échapper à tous les genres ainsi qu'à toutes les certitudes thématiques ou idéologiques.

Etre à fois déchiffreur et mémorialiste, c'est comprendre que l'œuvre saisit dans les nuances du devenir l'éclat de l'être. Le mémorialiste suit le cours du temps, la nuance du jour, la beauté et la tristesse passagère des instants livrés à l'oubli. Le mémorialiste, servant humble et déférent de Mnémosyme, recueille cette « matière première », au sens alchimique, dont le déchiffreur lui, se saisira avec cet esprit d'aventure qui caractérise les métaphysiciens et les hommes de cœur. Le mémorialiste investit le devenir de la puissance d'être de la mémoire, de la transmission, alors que le déchiffreur redonnera à la chose transmise, recueillie, sa chance de refleurir en d'autres contrées, plus subtiles et plus lumineuses. En d'autres termes, on pourrait dire que le mémorialiste construit un édifice de pensées, de réflexions, de savoirs qui permettront au déchiffreur de préfigurer le temple intérieur de la connaissance, que nous nommerons la « gnose poétique » et dont nous approchons par une connaissance de plus en plus précise, et précise jusqu'à l'éblouissement, de l'interdépendance universelle.

De livres en livres, Jünger poursuit cette œuvre de déchiffreur et de mémorialiste car loin de se soumettre à la lettre morte de ceux qui ne croient qu'au « travail du texte », sa pensée, toujours à la pointe de « l'esprit qui vivifie », cherche en toute chose, selon la formule de Nietzsche, « l'éternelle vivacité ». A celui qui voudra rendre justice à la pensée, toujours en mouvement, mais toujours exactement orientée, d'Ernst Jünger, l'occasion se présentera souvent de citer en une même phrase des auteurs, des théories, des méthodes que notre esprit compartimenteur, hérité d'une méconnaissance et d'une idolâtrie de la philosophie cartésienne, répugne à associer. Ainsi le Nouveau Testament et les « évangiles » subversifs du Solitaire d'Engadine, ou encore les références aux mondes bibliques ou païens, les méthodes scientifiques et les songeries hermétiques, la poésie et la guerre, l'aventure et l'immobilité contemplative.

Les historiographes de l'œuvre jüngérienne insistent, par exemple, sur les ruptures ou les revirements d'ordre idéologique ou politique. Certes, le nationalisme exacerbé et martial du jeune collaborateur d'Arminius cédera la place au Contemplateur solitaire, l'apologiste du Travailleur, accomplissant sa « Figure » par la technique, deviendra le critique avisé du monde moderne et l'inventeur de l'Anarque. Certes, l'intérêt pour les anciennes traditions païennes de l'Europe précède une méditation biblique. Mais aussitôt l'intelligence se dégage-t-elle de l'histoire proprement dite qu'elle voit dans ces diverses configurations se dessiner un paysage intérieur dont la cohérence et l'harmonie sont bien davantage la marque que le discord ou le chaos.

L'œuvre de Jünger, disions-nous, est l'une des moins narcissiques du vingtième siècle. Rarement tournée vers le « moi », elle est une invitation à découvrir le monde, « ce vaisseau cosmique » à bord duquel nous traversons le temps. L'aventure sociale ou psychologique tient une place infime dans cette œuvre qui est sans doute la première du vingtième siècle, au sens hiérarchique autant que chronologique, à s'être radicalement dégagée des méthodes et des théories du Naturalisme du dix-neuvième siècle, si abondamment relayé par la littérature des sciences humaines. Les groupes sociaux, la psychologie individuelle ou collective n'intéressent guère l'auteur des Falaises de Marbre ou d'Eumeswil. Bien davantage son attention est-elle requise par les rêves lorsque les rêves révèlent la nature héraldique et sacrée du monde.

Maintes fois mis en accusation, Jünger n'a jamais cherché aucune caution de « bonne moralité » politique, son œuvre se situant résolument, dans sa part la plus importante, du côté de l'intemporel. On risque fort de ne rien comprendre à son Journal si l'on ne voit pas que le temps, son temps, est toujours considéré du point de vue de l'intemporel. L'observation exacte prend place dans une vue-du-monde qui dénie au hasard et à la nécessité l'empire que la pensée moderne leur accorde.

« L'existence des choses, écrit Jünger, est donc préfigurée comme dans un sceau dont la figure imprimée dans la cire apparaît plus ou moins distinctement. » Il ne semble pas que, sur ce point, la pensée de Jünger ait varié. On songe irrésistiblement au début fameux des Disciples à Saïs de Novalis: « Les hommes marchent par des chemins divers. Qui les suit et les compare verra naître d'étranges figures; figures qui semblent appartenir à cette grande écriture chiffrée qu'on rencontre partout: sur les ailes, sur la coque des oeufs, dans les nuages, dans la neige, dans les cristaux, dans les formes des rocs, sur les eaux congelées, à l'intérieur et à l'extérieur des montagnes, des plantes, des animaux, des hommes, dans les clartés du ciel, sur les disques de verre et de poix lorsqu'on les frotte et lorsqu'on les attouche: dans les limailles qui entourent l'aimant, et dans les étranges conjonctures du hasard.. »

Les Figures, les Types, les Formes témoignent d'une pensée pour laquelle la création littéraire est un moyen de connaissance, une gnose. L'engagement héroïque des premiers temps n'est point contraire à l'engagement, plus radical encore, de l'Anarque et du Contemplateur, si l'on comprend, comme l'enseigne la Bhagavât-Gîta que la contemplation est une forme supérieure de l'action. La forme supérieure ne renie point la forme dépassée, elle la couronne, tout comme l'ontologie dont nous parle Heidegger couronne la métaphysique qu'elle dépasse. Bien plus que des ruptures, le lecteur qui entrevoit dans l'œuvre de Jünger un moyen de connaissance, sera enclin à voir des changements d'états, comme dans les « œuvres » des Alchimistes. Car si l'œuvre de Jünger est éloignée du Naturalisme de Zola, elle est, en revanche, fort proche des « philosophes de la nature » tels que Franz von Baader, qui eurent une influence non négligeable sur les Romantiques allemands d'Iéna.

Alchimistes et théosophes dans la lignée de Paracelse et de Jacob Böhme, les philosophes de la nature s'avancent dans la connaissance comme sur un chemin où se lèvent les intersignes, légers comme des cicindèles. A chaque signe, le voyageur est convié à un changement d'état de conscience qui renvoie à un changement d'état d'être. Les Figures du monde visible sont l'empreinte d'un sceau invisible et les circonstances de notre existence, en ce qu'elles ont de resplendissant, témoignent, elles aussi, de cette concordance entre les mondes qui justifie l'existence des symboles.

Dans un monde où les symboles accomplissent leur fonction pontificale, ni le hasard ni le déterminisme n'ont cours; le monde s'ordonne selon des principes qui, pour être hors d'atteinte de l'entendement humain, n'en sont pas moins à l'origine des plus pertinentes interprétations humaines. Alors que le déterministe explique l'homme et le monde comme des mécanismes, obéissant ainsi, plus ou moins à son insu, à une morale utilitaire, Jünger appartient à la tradition, largement menacée mais cependant persistante, du romantisme « roman » de Novalis qui s'adonne à l'interprétation infinie, au « buisson ardent » de l'herméneutique permanente. Dans la vue du monde esthétique et métaphysique de Jünger, le monde n'étant point soumis à l'utilité, sa valeur ne dépendant point de son usage, de même que selon une éthique chevaleresque, la fin ne justifie jamais les moyens, la finalité n'est jamais que dans le cœur secret des êtres et des choses, dans cette plus incandescente limpidité que nous laissent deviner les approches et les dialogues avec l'invisible.

La danse de la cicindèle est l'idéogramme clair de la pure présence de l'être à lui-même. Tel est le sacré, le numineux, pour reprendre le mot de Walter Otto, dont l'approche exige la plus grande délicatesse. La connaissance du monde, la gnose poétique, est avant tout une philocalie. Le sacré, le divin se révèlent dans la beauté car la beauté est l'approche du sens. Là où les choses prennent sens, la beauté transparaît. L'accusation d'esthétisme contre l'œuvre de Jünger traduit la courte vue de ceux qui la portent car la beauté est toujours, dans l'œuvre de Jünger, le signe d'une présence, d'une profondeur métaphysique, d'un autre monde, principe de profusion et de splendeur. Le monde des dieux, comme celui des fleurs et des papillons, est un monde dispendieux et imprévisible. L'homme de connaissance qui succède, dans la chronologie jüngérienne, à l'homme de puissance, s'avance dans l'assentiment à la beauté du monde comme « sceau héraldique » et dans le non moindre consentement à l'imprévisible. L'homme de connaissance est chasseur subtil. A l'affût sur l'orée, le chasseur subtil reçoit les signes qui, dans le visible, sont la marque de l'invisible, et ses rêves ont leur part, qui n'est rien moins que négligeable, dans la connaissance effective du monde.

La rupture inaugurale avec le monde bourgeois va d'emblée orienter l'œuvre de Jünger vers des régions extrêmes qui échappent à la fois à l'attention et au contrôle du monde moderne. L'exploration du monde intérieur n'est pas, chez Jünger, la complaisance narcissique de la subjectivité pour elle-même mais une traversée aussi exacte et impersonnelle qu'un voyage entomologique dans le monde extérieur. La psychologie jüngérienne ne relève pas de la « psyché » profane, larvaire, mais de la « psyché », en tant qu'âme, au sens néoplatonicien. Notre âme, dans la gnose jüngérienne, n'est pas disjointe de l'Ame du monde. L'Ame du monde et ses symboles augustes transparaissent dans l'âme humaine, sous la forme des songes, des visions, des pressentiments. Le poète est familier de l'augure qui surprend sa pensée dans l'exercice de la plus grande exactitude. La gnose jüngérienne s'exerce avec une virtuosité rare, aussi bien sur le mode de l'ampleur: les mythes, les légendes, les vastes herméneutiques de l'histoire humaine et des textes sacrés, que dans celui de l'intensité: la minuscule mais exaltante trouvaille du chasseur de papillons qui concentre dans l'infime toutes les énergies explosives de sa quête.

Dans le célèbre tableau de Caspar David Friedrich Les Falaises de Rügen, l'immensité du site, sa solennité, donnent au mode de l'ampleur l'une de ses représentations picturales les plus achevées, parce que devant la vastitude, le vide, l'espace qui s'encastrent avec violence dans le paysage, un personnage vu de dos paraît ignorer l'infini de l'ampleur qui s'offre à lui pour s'attacher à l'infini de l'intensité de sa recherche d'herboriste ou de chasseur d'insecte. L'ampleur du vaste prend sa mesure par l'intensité de l'infime. La science des lettres, la science naturaliste ou historique devient métaphysique aussitôt qu'elle parvient à unir en elle le mode d'intensité et le mode d'ampleur, la dimension horizontale et la dimension verticale, l'empreinte, dont les marques sont plus ou moins visibles, et le sceau.

La logique de la gnose est différente de la logique de la science profane, en ce qu'elle ignore la finalité effective, utile, quantifiable. La gnose est à elle-même sa propre finalité, et le monde dont elle traite est un monde de qualités. La gnose ne dénombre pas seulement le réel, elle s'avance dans le déchiffrement. Déchiffrer le monde, c'est traverser le temps dans le vaisseau cosmique, et c'est œuvrer à la révélation du sens à travers les apparitions successives du monde. Le déterminisme philosophique, autant que la théorie du hasard, détournent notre entendement de la beauté et du mystère, de telle sorte à faire de nous les dociles serviteurs du monde moderne, et de ses morales utilitaires et puritaines. La gnose poétique de Jünger est la reconquête de la puissance et de l'immortalité dont la société, placée sous le signe de l'uniformité, nous dépossède. La gnose suppose une « transvaluation de toutes les valeurs », pour reprendre la formule Nietzsche que l'on pourrait aussi caractériser comme une subversion de la subversion établie par le tiers-état, dans la mesure où la reconquête de la « vie magnifique », de la puissance est le propre de la Figure, telle que la conçoit Jünger.

Jünger distingue deux conceptions de l'individu, par les mots allemands, Einzelne et individuum. Le mot individuum désignant l'individu à la fois égocentrique et interchangeable des sociétés de masse, alors que le mot Einzelne se rapporte à l'individu en tant que singularité et originalité irréductible, en tant que Figure. A l'individu perdu dans la masse et, par cela même farouchement attaché à ce qu'il croit être ses « biens » correspond une science calculante (pour reprendre le mot de Heidegger), alors que pour l'individu en tant que Figure, la science est méditative, et, par cela, accroissement de puissance. Pour Jünger, la connaissance accroît la Figure dans sa distinction et son intensité. Les lignes deviennent plus précises et les couleurs plus rayonnantes. La gnose est poétique, au sens de l'étymologie grecque, du « faire » qui laisse l'empreinte la plus précise possible. Par la gnose jüngérienne, nous entrons dans une perspective hiérarchique, où la logique de cause et d'effet, et avec elle toutes les formes de progressisme, de déterminisme ou d'évolutionnisme sont dépassées: « L'ordre hiérarchique dans le domaine de la Figure ne résulte pas de la loi de cause à effet mais d'une loi tout à fait autre, celle du sceau et de l'empreinte ». Dans cette logique, nouvelle par rapport aux deux siècles précédents mais, nous y reviendrons, dans un sens plus profond, traditionnelle, ce qui importe n'est pas seulement ce qui nous précède et ce qui s'annonce mais, plus décisivement, ce qui nous surplombe, le sceau dont nous sommes l'empreinte.

Cette logique gnostique, et héraldique, pour célébratrice qu'elle soit de la splendeur du monde, pour approbatrice qu'elle soit de la puissance, et du rayonnement de la Figure, n'en témoigne pas moins d'une forme d'humilité essentielle. Le moderne, qui affiche partout sa modestie et son profil bas, tient pourtant farouchement à être le producteur de tout, et à cette fin, il renie Dieu et les dieux, les Muses et les messagers célestes, de sorte à n'être qu'à lui-même redevable de ses « travaux ». Cette étrange démesure, au sens exact outrecuidante, enferme l'individu en lui-même et laisse ses œuvres comme les objets aléatoires de son narcissisme navrant. Le nihilisme moderne n'est autre que la considération pathétique de cette impuissance vaniteuse à connaître le monde. Dans la perspective métaphysique propre à la théorie des signatures et des empreintes dont nous constatons la fécondité dans l'œuvre de Jünger, l'humilité consiste à reconnaître que nos idées et nos visions ne nous appartiennent pas en propre, qu'elles proviennent de l'intemporel, auquel nous donnent accès notre grandeur d'âme et notre acuité intellectuelle. La gnose poétique considère dans le singulier et dans le multiple les Figures d'éternité dont ils procèdent. Elle est dépassement du nihilisme car elle est recouvrance de la possibilité magnifique qui nous fut donnée in illo tempore, puis ôtée, d'atteindre poétiquement à la connaissance, non par projection ou reflet, mais par des actes de puissance et de beauté tels qu'ils adviennent dans Virgile, dans l'ivresse du songe de la « race d'or ». Dépasser le nihilisme, c'est aller, au pas qui ré-enchante les apparences, vers les contrées éclatantes où l'individu s'accorde à la Figure, où les pressentiments s'accomplissent, dans des œuvres qui seront la preuve de notre humilité.

Alors que le moderne se veut sans Dieu ni Maître, proclame la relativité du Vrai et du Beau non sans faire de sa médiocrité la mesure universelle, jugeant toute création superflue et toute connaissance impossible, la Figure trouve sa mesure par la création et sa connaissance par l'oubli de l'individualité, au sens quantitatif et profane. Aussitôt qu'il est question de connaissance et de poésie, il faut s'interroger sur la provenance et le destinataire de cette poésie et de cette connaissance. Tout ne s'adresse pas à n'importe qui. L'angle d'approche détermine la destination du message diplomatique, car toute métaphysique est diplomatie et les auteurs, au sens latin et étymologique, d'auctor qui se réfère à l'auctoritas, - la « vertu qui accroît », comme le rappelle Philippe Barthelet, - sont ambassadeurs entre les suavités immanentes des corolles et des parfums du jardin sous la pluie d'été au crépuscule et les contrées transcendantes où les dieux apparaissent.

Le grief le plus persistant que les modernes cultivent à l'égard de la gnose est d'être « élitiste », de ne s'adresser, selon la formule stendhalienne, qu'aux « rares heureux », de dédaigner les laborieuses et méritantes majorités. Grief inepte car il n'est rien de plus généreux, de plus disponible, de plus accueillant que le livre qui s'offre à chacun, sans jamais prétendre à contraindre le plus grand nombre. La gnose requiert des dispositions particulières, ou, disons, une orientation de l'Intellect, mais elle confère cette orientation autant qu'elle l'exige. Alors que la société, aussi « démocratique » qu'elle se veuille ne cesse de nous imposer des limites et des conditions auxquelles nous ne pouvons-nous soustraire, la gnose, et surtout la gnose dont l'humilité consiste à se traduire en œuvres, offre à qui le désire avec ardeur, l'aventure du Sans-Limite, c'est-à-dire la traversée odysséenne de la Figure à travers les ordres du monde jusqu'à sa perception la plus lumineuse, éclat d'éternité sur la surface des eaux.

La gnose, dans son exercice le plus accompli, est un privilège mais c'est un privilège offert à qui voudra bien s'en saisir, alors que nous vivons dans un monde constitué d'avantages qui sont la récompense de la cupidité et de la vilenie. Il n'est pas impossible, et nous y reviendrons, qu'il y eût aussi quelque rapport entre la gnose poétique et la philosophie politique. Les Figures du Travailleur, du Rebelle et de l'Anarque, qui se succèdent dans l'œuvre de Jünger, approfondissent, si l'on prend la peine de les considérer en perspective, une méditation sur le siècle mais aussi une méditation sur l'art de vivre, non plus de l'individu de l'ère bourgeoise mais de l'individu (Einzelne) qui cherche à conserver sa Figure au sein du monde de la technique qui, loin de s'affirmer comme l'expression de la puissance, au sens nietzschéen, comme on pouvait encore le croire au début du siècle, paraît au contraire avoir pour objectif le contrôle et l'annihilation de toute puissance libre.

Face à la technique d'une « mondialisation » dont chacun sait bien qu'elle n'est qu'une américanisation cybernétique, l'œuvre de Jünger, dans son exigence poétique et gnostique peut se lire comme un traité de résistance au nihilisme. Le Travailleur oeuvrait à vaincre le mal par le mal, selon le principe de Paracelse, et à porter contre le nihilisme les armes les mieux trempées du nihilisme lui-même. Il « travaillait » ainsi selon les périlleuses procédures de l'oeuvre-au-noir, à l'implosion d'une situation intenable, et à ouvrir la voie de la contemplation. Les sentes forestières qu'ouvrent les audaces du Rebelle et de l'Anarque seront, elles, l'initiation à d'autres couleurs. Au « noir et blanc » de l'intensité expressionniste des premières œuvres, si mal comprises, succédera le versicolore armorial des Songes et des Visions des Falaises de Marbre et de Visite à Godenholm. Le combat par le fer et le feu du guerrier cède la place aux guerres plus subtiles dont les conquêtes sont des états de conscience. L'intensité, et telle est bien la clef de voûte de la gnose poétique d'Ernst Jünger, s'accroît d'œuvre et œuvre comme une réalisation, au sens initiatique, d'une exactitude herméneutique qui perçoit, à l'apogée de la vitesse et du mouvement, le grand silence et la grande immobilité.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

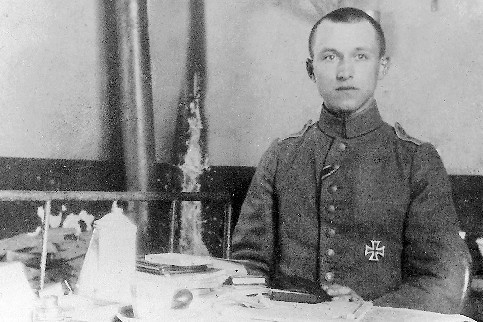

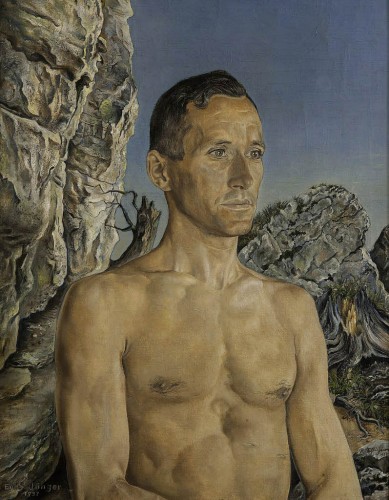

Digg La aventura de Jünger cobra el símbolo de una organicidad rotunda enla relación social del intelectual con la producción de una clase concreta; se trata fundamentalmente de una personalidad que de alguna manera expresa Drieu la Rochelle: ”(es) el hombre de mano comunista, el hombre de las ciudades, neurasténico, excitado por el ejemplo de los fascios italianos, así como por el de los mercenarios de las guerras chinas, de los soldados de la Legión Extranjera” (8). Se verdadera patria son las llamas, la tensión del combate, la experiencia de la guerra. Su conformación íntima se encuentra manifestada en otro de aquellos que vivieron ”la encarnación de una civilización en sus últimas etapas de decadencia y disolución”, así dice Ernst Von Salomon en Los proscritos: ”sufríamos al sentir que en medio del torbellino y pese a todos los acontecimientos, las fatalidades, la verdad y la realidad siempre estaban ausentes” (9). Es este el territorio en que Jünger preparará la red invisible de su obra, recogiendo las brasas, los escombros, las banderas rotas. Cuando todo en Alemania se tambalea: se cimbran los valores humanitarios y cristianos, la burguesía se declara en bancarrota y los espartaquistas establecen la efímera República de Münich, aparecen los elementos vitales de su escritura, que atesorará como una trinchera imbatible heredera del limo, con la llave precisa que abrirá las puertas de la putrefacción a la literatura.

La aventura de Jünger cobra el símbolo de una organicidad rotunda enla relación social del intelectual con la producción de una clase concreta; se trata fundamentalmente de una personalidad que de alguna manera expresa Drieu la Rochelle: ”(es) el hombre de mano comunista, el hombre de las ciudades, neurasténico, excitado por el ejemplo de los fascios italianos, así como por el de los mercenarios de las guerras chinas, de los soldados de la Legión Extranjera” (8). Se verdadera patria son las llamas, la tensión del combate, la experiencia de la guerra. Su conformación íntima se encuentra manifestada en otro de aquellos que vivieron ”la encarnación de una civilización en sus últimas etapas de decadencia y disolución”, así dice Ernst Von Salomon en Los proscritos: ”sufríamos al sentir que en medio del torbellino y pese a todos los acontecimientos, las fatalidades, la verdad y la realidad siempre estaban ausentes” (9). Es este el territorio en que Jünger preparará la red invisible de su obra, recogiendo las brasas, los escombros, las banderas rotas. Cuando todo en Alemania se tambalea: se cimbran los valores humanitarios y cristianos, la burguesía se declara en bancarrota y los espartaquistas establecen la efímera República de Münich, aparecen los elementos vitales de su escritura, que atesorará como una trinchera imbatible heredera del limo, con la llave precisa que abrirá las puertas de la putrefacción a la literatura.

Le Cœur aventureux jüngérien est appelé à se faire précurseur et à suivre « le chemin d'une certaine astreinte ». La raison n'est pas congédiée mais interrogée; elle n'est point récusée, en faveur de son en-deçà mais requise à une astreinte nouvelle qui rend caduque les définitions, les descriptions, les discriminations dont elle se contentait jusqu'alors. « Que l'hégémonie de la raison s'établisse comme la rationalisation de tous les ordres, comme la normalisation, comme le nivellement, et cela dans le sillage du nihilisme européen, c'est là quelque chose qui donne autant à penser que la tentative de fuite vers l'irrationnel qui lui correspond. » A celui qui se tient sur la ligne, en précurseur et soumis à une astreinte nouvelle, il est donné de voir le rationnel et l'irrationnel comme deux formes concomitantes de superstition.

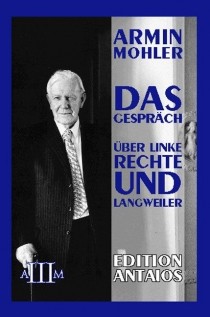

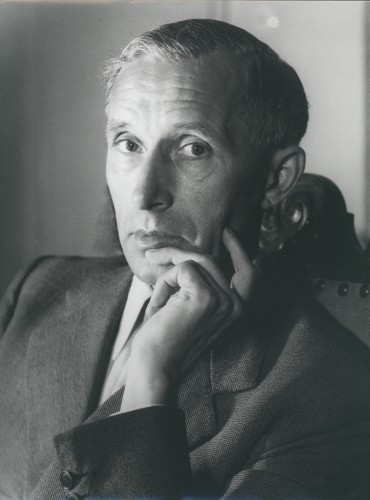

Le Cœur aventureux jüngérien est appelé à se faire précurseur et à suivre « le chemin d'une certaine astreinte ». La raison n'est pas congédiée mais interrogée; elle n'est point récusée, en faveur de son en-deçà mais requise à une astreinte nouvelle qui rend caduque les définitions, les descriptions, les discriminations dont elle se contentait jusqu'alors. « Que l'hégémonie de la raison s'établisse comme la rationalisation de tous les ordres, comme la normalisation, comme le nivellement, et cela dans le sillage du nihilisme européen, c'est là quelque chose qui donne autant à penser que la tentative de fuite vers l'irrationnel qui lui correspond. » A celui qui se tient sur la ligne, en précurseur et soumis à une astreinte nouvelle, il est donné de voir le rationnel et l'irrationnel comme deux formes concomitantes de superstition.  Die Beziehung zwischen Ernst Jünger und Armin Mohler hat sich über mehr als fünf Jahrzehnte erstreckt. Sie wird – wenn in der Literatur erwähnt – als Teil der Biographie Jüngers behandelt. Man hebt auf Mohlers Arbeit als Jüngers Sekretär ab und gelegentlich auf das Zerwürfnis zwischen beiden. Mit den Wilflinger Jahren hatte dieser Streit nichts zu tun. Seine Ursache waren Meinungsverschiedenheiten über die erste Ausgabe der Werke Jüngers. Der Konflikt beendete für lange das Gespräch der beiden, das mit einer Korrespondenz begonnen hatte, im direkten Austausch und dann wieder im – manchmal täglichen – Briefwechsel zwischen der Oberförsterei und dem neuen französischen Domizil Mohlers in Bourg-la-Reine fortgesetzt wurde. Von 1949, als Mohler seinen Posten in Ravensburg antrat, bis 1955, als Jünger seinen 60. Geburtstag feierte, war ihre Verbindung am intensivsten, aber es gab auch eine Vor- und eine Nachgeschichte von Bedeutung.

Die Beziehung zwischen Ernst Jünger und Armin Mohler hat sich über mehr als fünf Jahrzehnte erstreckt. Sie wird – wenn in der Literatur erwähnt – als Teil der Biographie Jüngers behandelt. Man hebt auf Mohlers Arbeit als Jüngers Sekretär ab und gelegentlich auf das Zerwürfnis zwischen beiden. Mit den Wilflinger Jahren hatte dieser Streit nichts zu tun. Seine Ursache waren Meinungsverschiedenheiten über die erste Ausgabe der Werke Jüngers. Der Konflikt beendete für lange das Gespräch der beiden, das mit einer Korrespondenz begonnen hatte, im direkten Austausch und dann wieder im – manchmal täglichen – Briefwechsel zwischen der Oberförsterei und dem neuen französischen Domizil Mohlers in Bourg-la-Reine fortgesetzt wurde. Von 1949, als Mohler seinen Posten in Ravensburg antrat, bis 1955, als Jünger seinen 60. Geburtstag feierte, war ihre Verbindung am intensivsten, aber es gab auch eine Vor- und eine Nachgeschichte von Bedeutung. Mohler betrachtete den Waldgang vor allem als erste politische Stellungnahme Jüngers nach dem Zusammenbruch, eine notwendige Stellungnahme auch deshalb, weil die Strahlungen und die darin enthaltene Auseinandersetzung mit den Verbrechen der NS-Zeit viele Leser Jüngers befremdet hatte. In der aufgeheizten Atmosphäre der Schulddebatten fürchteten sie, Jünger habe die Seiten gewechselt und wolle sich den Siegern andienen; Mohler vermerkte, daß in Wilflingen kartonweise Briefe standen, deren Absender Unverständnis und Ablehnung zum Ausdruck brachten.

Mohler betrachtete den Waldgang vor allem als erste politische Stellungnahme Jüngers nach dem Zusammenbruch, eine notwendige Stellungnahme auch deshalb, weil die Strahlungen und die darin enthaltene Auseinandersetzung mit den Verbrechen der NS-Zeit viele Leser Jüngers befremdet hatte. In der aufgeheizten Atmosphäre der Schulddebatten fürchteten sie, Jünger habe die Seiten gewechselt und wolle sich den Siegern andienen; Mohler vermerkte, daß in Wilflingen kartonweise Briefe standen, deren Absender Unverständnis und Ablehnung zum Ausdruck brachten. di Luigi Iannone

di Luigi Iannone

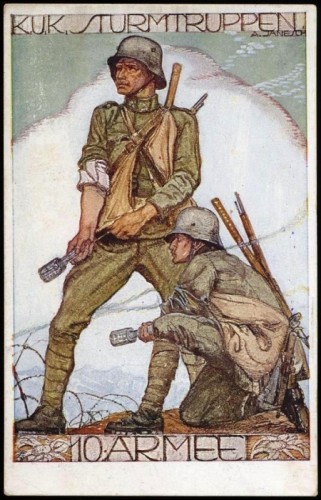

Por ello, si su texto La Guerra, nuestra madre escrito en 1934 ha recorrido una suerte semejante a Bagatelas para una masacre de Louis Ferdinand Céline, en el sentido de que ambos son unánimemente ”condenados” y prácticamente inencontrables a excepción de fragmentos; el joven escritor alemán, que afirmaba que: ” la voluptuosidad de la sangre flota por encima de la guerra como una vela roja sobre una galera sombría” (3), es el mismo que canta el poder de la sangre, treinta y un años después de cieno, fuego y derrota: ”los gigantescos cristales tienen forma de lanzas y cuchillos, como espadas de colores grises y violetas, cuyos filos se han templado en el ardiente soplo de fuego de fraguas cósmicas” (4).

Por ello, si su texto La Guerra, nuestra madre escrito en 1934 ha recorrido una suerte semejante a Bagatelas para una masacre de Louis Ferdinand Céline, en el sentido de que ambos son unánimemente ”condenados” y prácticamente inencontrables a excepción de fragmentos; el joven escritor alemán, que afirmaba que: ” la voluptuosidad de la sangre flota por encima de la guerra como una vela roja sobre una galera sombría” (3), es el mismo que canta el poder de la sangre, treinta y un años después de cieno, fuego y derrota: ”los gigantescos cristales tienen forma de lanzas y cuchillos, como espadas de colores grises y violetas, cuyos filos se han templado en el ardiente soplo de fuego de fraguas cósmicas” (4).

Das Wort „Endzeiten“ erinnert an die biblischen Voraussagen über einen linearen Zeitverlauf, der in ein apokalyptisches Ende der Welt einmünden soll. Diese Idee ist typisch für den Offenbarungsmenschen, dessen Denken aus semitischen Quellen gespeist wird: „Dann sah ich einen neuen Himmel und eine neue Erde. Der erste Himmel und die erste Erde waren verschwunden, und das Meer war nicht mehr da. Ich sah, wie die Heilige Stadt, das neue Jerusalem, von Gott aus dem Himmel herabkam“

Das Wort „Endzeiten“ erinnert an die biblischen Voraussagen über einen linearen Zeitverlauf, der in ein apokalyptisches Ende der Welt einmünden soll. Diese Idee ist typisch für den Offenbarungsmenschen, dessen Denken aus semitischen Quellen gespeist wird: „Dann sah ich einen neuen Himmel und eine neue Erde. Der erste Himmel und die erste Erde waren verschwunden, und das Meer war nicht mehr da. Ich sah, wie die Heilige Stadt, das neue Jerusalem, von Gott aus dem Himmel herabkam“

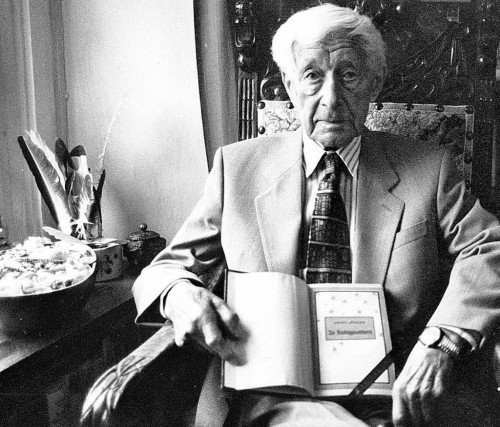

Ernst Jünger says in his acceptance speech for the prestigious Goethe prize in 1982, "I've had the experience that one meets the best comrades in no-man's-land. I've always been pleased with my troops (Mannschaft) in war and my readership in peace. A hand that holds a weapon with honor, holds a pen with honor. It is stronger than any atom bomb, or any rotary press." With these words Jünger bestows an honour on us, his readership. He equates us with his comrades-in-arms in times of peace, but is it a wonder after all? If you are a reader of Ernst Jünger, you must be in either one of two camps, those who consider his opus with genuine admiration or the detractors, those sceptics, "whose contribution does not equal to one blade of grass, one mosquito wing".

Ernst Jünger says in his acceptance speech for the prestigious Goethe prize in 1982, "I've had the experience that one meets the best comrades in no-man's-land. I've always been pleased with my troops (Mannschaft) in war and my readership in peace. A hand that holds a weapon with honor, holds a pen with honor. It is stronger than any atom bomb, or any rotary press." With these words Jünger bestows an honour on us, his readership. He equates us with his comrades-in-arms in times of peace, but is it a wonder after all? If you are a reader of Ernst Jünger, you must be in either one of two camps, those who consider his opus with genuine admiration or the detractors, those sceptics, "whose contribution does not equal to one blade of grass, one mosquito wing".

O “mito”, como a “representação de uma batalha”, surge espontaneamente e exerce um efeito mobilizador sobre as massas, incute-lhes uma “fé” e torna-as capazes de actos heróicos, funda uma nova ética: essas são as pedras angulares do pensamento de Georges Sorel (1847-1922). Este teórico político, pelos seus artigos e pelos seus livros, publicados antes da primeira guerra mundial, exerceu uma influência perturbante tanto sobre os socialistas como sobre os nacionalistas.

O “mito”, como a “representação de uma batalha”, surge espontaneamente e exerce um efeito mobilizador sobre as massas, incute-lhes uma “fé” e torna-as capazes de actos heróicos, funda uma nova ética: essas são as pedras angulares do pensamento de Georges Sorel (1847-1922). Este teórico político, pelos seus artigos e pelos seus livros, publicados antes da primeira guerra mundial, exerceu uma influência perturbante tanto sobre os socialistas como sobre os nacionalistas.

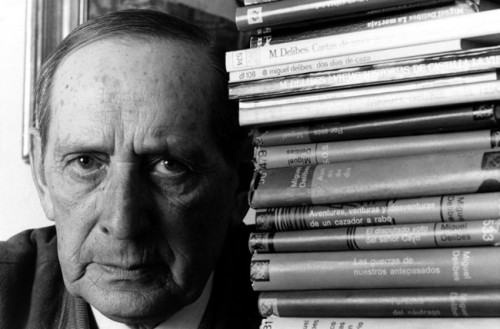

Ernst Jünger: yo soy la acción

por José Luis Ontiveros

Ex: http://culturatransversal.wordpress.com

En torno a la obra del escritor alemán Ernst Jünger se ha producido una polémica semejante a la que preocupó a los teólogos españoles en relación con la existencia del alma de los indios. De alguna manera, el hecho de que se le haya discutido en medios intelectuales mundiales con asiduidad, y el que una nueva política literaria tienda a revalorizarlo, le otorga, como lo hizo a los naturales el Papa Paulo III, la posibilidad de una lectura conversa; ya no traumatizada por su historia maldita, absolutoria de su derecho a la diferencia, y exoneradora de un pasado marcado por la gloria y la inmundicia.